Seven months ago, the U.S. closed a massive loophole that let foreign companies ship goods into America duty-free. Since May 2025, CBP has collected over $1 billion in duties on 246 million low-value packages that previously entered without inspection or tariffs.

This isn’t just revenue. This is a fundamental shift in how goods enter the country—and what gets through.

What De Minimis Actually Was

For decades, the U.S. had a rule: packages under $800 could enter the country duty-free and skip certain inspections. The logic was simple—the cost of inspecting cheap goods exceeded their value.

But that loophole became a highway for criminals, counterfeiters, and companies dodging tariffs.

A company in China could ship $799 worth of counterfeits to the U.S. It would arrive duty-free with minimal inspection. No tariffs owed. No documentation required. No real vetting of what was inside.

Multiply that by millions of shipments daily, and you have a massive blind spot in U.S. trade enforcement.

The Phaseout: Two Stages

The administration didn’t flip a switch overnight. They did this strategically:

May 2, 2025: De minimis ended for packages from China and Hong Kong. These two countries represent the largest volume of low-value imports. The change was immediate and significant.

August 29, 2025: De minimis ended worldwide for all countries. Now every package under $800 gets inspected and subject to duties.

The phased approach gave importers time to adjust. It also showed the impact: May to August results helped justify the full implementation.

The $1 Billion Reality

In seven months, CBP collected $1 billion in duties on 246 million packages. That’s roughly $4 per package on average.

Those duties represent:

Money that previously went uncollected—it’s not new tax burden, it’s closing a loophole where companies legally avoided paying what they owed.

Revenue flowing into the U.S. Treasury instead of bypassing the system entirely.

Economic pressure on foreign competitors who can’t undercut American businesses with duty-free goods anymore.

“Reaching the $1 billion milestone so quickly shows just how much revenue was slipping away under the old rules,” said CBP Commissioner Rodney S. Scott. “With this change, American businesses don’t have to compete with duty-free foreign goods, and CBP has stronger oversight of what comes into our country.”

That’s the core issue: American manufacturers were competing against duty-free foreign imports. Now that’s over.

The Safety Increase: 82% More Seizures

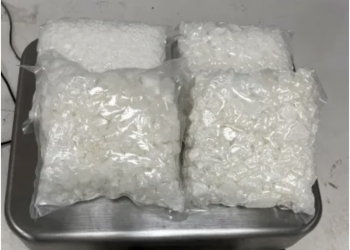

Here’s what matters beyond money: seizures of unsafe and non-compliant goods increased 82% since the de minimis loophole closed.

What’s being caught:

Counterfeit products—fake electronics, knockoff goods, designer fakes. Counterfeiters loved de minimis because they could ship small quantities repeatedly without detection.

Narcotics—fentanyl, methamphetamine, and other drugs hidden in low-value shipments. The volume was too high to inspect everything. Now CBP is catching them.

Faulty electronics—devices with safety issues that never would have passed inspection. Computers with faulty batteries. Chargers that overheat. Devices that catch fire.

Hazardous chemicals—lead paint on children’s toys, toxic materials in clothing, substances banned by EPA in products marketed as safe.

Without de minimis enforcement, these products reached American consumers. Now they’re being stopped.

How This Actually Works

When a package arrives at the port, CBP now:

Scans and documents every shipment (previously, most low-value shipments were waved through).

Collects duties based on actual value and product classification (previously, duty-free).

Inspects high-risk shipments (previously, minimal inspection).

Uses data and intelligence to flag suspicious patterns (previously, limited visibility).

The visibility is the game-changer. When CBP inspected a fraction of packages, criminals operated in the blind spots. Now CBP sees what’s coming.

“With increased visibility into data for these low-value shipments, we’re better equipped to detect and disrupt criminal networks from smuggling drugs, counterfeits, and other illegal items,” said Acting Executive Assistant Commissioner Susan S. Thomas. “Making our country safer.”

The Business Impact

American importers and businesses now compete on a level playing field. A U.S. manufacturer competing against a Chinese company no longer faces the disadvantage of duty-free competition.

Prices may change. Some cheap goods will become more expensive because duties are now applied. But prices were already artificially deflated because foreign competitors weren’t paying duties.

Legitimate importers appreciate the clarity. They always had to pay duties. Now their competitors do too.

E-commerce companies adapting their supply chains. Some are shifting suppliers to duty-advantaged countries. Some are absorbing costs. Some are adjusting pricing.

It’s an adjustment, but it’s a fair one.

The Volume Numbers

246 million packages in seven months. That’s 35 million packages per month being processed with full inspection and duty collection.

The volume keeps growing as importers adapt. Some are consolidating shipments to reach the $800 threshold (now subject to duties anyway). Some are shifting to different suppliers. Some are just accepting the new cost structure.

But the volume shows the scale of the de minimis loophole that just closed. Hundreds of millions of packages that previously entered with minimal oversight now get full attention.

The Criminal Network Impact

Counterfeiters, drug smugglers, and smuggling organizations depended on de minimis. The massive volume and minimal inspection meant some percentage of shipments would get through. It was a numbers game.

Now that game is over. Every shipment gets documented. Every shipment gets assigned duties. High-risk shipments get inspected.

“The end of the de minimis exemption aligns with CBP’s broader trade enforcement initiatives aimed at ensuring compliance with U.S. customs regulations and safeguarding domestic industries,” according to CBP official statements.

That’s CBP saying: we’re not just collecting revenue, we’re dismantling the infrastructure that enabled smuggling.

The Complexity for Importers

The change isn’t seamless. Importers now have to:

Properly classify products (instead of listing them generically).

Accurately declare value (instead of undervaluing to stay under $800).

Provide documentation (instead of minimal paperwork).

Expect duty collection (instead of duty-free entry).

CBP provides guidance through their E-Commerce and De Minimis FAQ page. But compliance requires work—and that’s the point. It’s supposed to require work so bad actors face higher barriers.

International Implications

Other countries are watching this. The U.S. closing the de minimis loophole affects global trade patterns. Exporters who relied on duty-free entry to the U.S. market now face tariffs.

Some countries may close their own loopholes in response. Some may challenge the U.S. change through trade mechanisms. Some will just adapt.

But the signal is clear: the U.S. is closing loopholes that undermine trade enforcement and domestic industry protection.

The Revenue Question

$1 billion in duties collected raises a policy question: where does this money go?

Tariff revenue flows to the U.S. Treasury. The Trump administration has historically used tariff revenue for border security funding, infrastructure, and debt reduction. Congress determines ultimate allocation.

But the point isn’t just the money. It’s closing a enforcement gap that enabled counterfeiting, drug smuggling, and unfair competition.

What This Means Going Forward

CBP is now capable of:

Full visibility into low-value shipments (previously blind spot).

Duty collection on goods that previously avoided tariffs (previously uncollected revenue).

Seizure of dangerous goods at higher rates (82% increase in seizures).

Detection of criminal networks operating through multiple small shipments (previously invisible in aggregate).

The de minimis loophole is closed. The change is implemented globally. CBP has full authority and infrastructure to enforce it.

The Bottom Line

CBP collected $1 billion in duties on 246 million low-value packages in seven months since closing the de minimis loophole. The change increased seizures of counterfeit and dangerous goods by 82%.

This represents both significant revenue recovery and major enforcement capability improvement. It closes a loophole that criminals and unfair competitors exploited for decades.

The change is implemented. The infrastructure is operational. The results are measurable.

American businesses now compete without the disadvantage of duty-free foreign competition. American consumers are safer because more dangerous goods are being intercepted. American government is collecting revenue that previously slipped away.

It’s a fundamental shift in how goods enter the country—and who bears the cost of that entry.