This year marks the 45th anniversary of ballooning in Plano and Collin County.

The event took place at Oak Point Park and Nature Preserve, at the Red Tail Pavilion in Plano, Texas, where crowds gathered to marvel at the vibrant display of hot air balloons.

Running from Thursday to Sunday, September 19th to 22nd, the festival offered a wide range of activities for visitors of all ages. Attendees enjoyed live entertainment on the main stage, special activities for kids, skydiving shows, and an array of food vendors. There were also stands featuring handmade merchandise. The highlight of the event, of course, was the breathtaking sight of hot air balloons rising into the sky.

How It All Started:

Hot air ballooning began about 200 years ago with the invention of the first balloon by two papermakers, the Montgolfier brothers, from the small town of Annonay in southern France. Fascinated by how smoke rose from the fire, they set out to harness this lifting power using balloons made from paper and cotton. Although they mistakenly believed smoke itself caused the lift, they nevertheless succeeded in creating the world’s first hot-air balloon.

On June 5th, 1783, the Montgolfier brothers demonstrated their invention to the townspeople of Annonay by launching an unmanned balloon. Inflated over a fire of bundled straw, the balloon was released into the town square. Their experiments continued, and they soon sent a sheep, a duck, and a rooster into the air in their balloon, where the animals stayed aloft for fifteen minutes. After the animals landed safely, the brothers were ready to take the next step—human flight.

However, they first needed permission from the King of France. Louis XVI, worried about the potential risk, decreed that the brothers should make the ascent themselves. If they survived, they would be pardoned, but if not, they could face consequences.

Unsettled by this harsh proposal, the Montgolfiers petitioned court officials and convinced the King to change his mind. On November 21st, 1783, in front of a cheering crowd in Paris, a brightly decorated balloon took flight, carrying the first human passengers: Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis d’Arlandes.

The balloon that carried the two aeronauts was kept aloft by heat from a straw fire, which was contained in a brazier hanging beneath its opening. As they drifted in a circle around a narrow gallery, the gentlemen found themselves constantly tending the flame or extinguishing small fires caused by stray embers. Using a wet sponge tied to the end of a long stick, they diligently put out the little blazes on their paper-and-cotton balloon.

Despite these challenges, the Duke d’Arlandes couldn’t help but admire the beauty of the scenery below. However, Pilâtre de Rozier, aware of their precarious situation, reminded his companion of the urgency: “If you keep looking at the river like that, you’ll be bathing in it soon!”

Despite the hazards, the balloon safely touched down after 30 minutes of flight, completing their historic journey through the air.

A Change to Lift Off!

In an uncanny twist of fate, other would-be aeronauts were working on the same goal of manned flight but from a different angle. Another Frenchman, Professor Charles, had been following Michael Faraday’s work with hydrogen gas, which, due to its widely spaced molecules, is less dense and lighter than air.

Charles joined forces with the Robert brothers in Paris, and together, they constructed a rubberized silk balloon filled with enough hydrogen to lift a basket carrying two people.

Though they were beaten to the skies by the Montgolfier brothers, the team was undeterred. Just ten days later, the citizens of Paris gathered for another historic flight. This time, a gas balloon carried Professor Charles and M. Robert into the air, reaching an impressive altitude of 1,800 feet. The flight was a triumph, and Charles was so captivated by the experience that when they landed and Robert stepped out, the balloon suddenly shot back into the sky. At that moment, Charles became the first person to witness two sunsets in one day.

Balloons on the Rage:

From France to the rest of Europe, the discovery of hot air balloons captivated the public, quickly becoming a sensation. However, a debate arose: Which was superior, the Montgolfier hot-air balloon or the Charlière gas balloon? This question would soon find its answer.

While the Montgolfier balloon was a delicate craft, the Charlière proved to be more robust. As a result, for nearly two centuries, the gas balloon reigned supreme as the king of lighter-than-air flight.

Some Mishaps Did Happen…

Pilâtre de Rozier believed he could combine the best features of both types of balloons. 1785, he attempted to cross the English Channel by mounting a gas balloon above a hot-air cylinder. However, he failed to fully understand the danger of having highly explosive hydrogen near an open flame. Tragically, the balloon caught fire and was destroyed near the French coast, making de Rozier not only the first aeronaut but also the first fatality in the history of air travel.

The Showmen:

Though novel to the world, balloons as a means of transportation were limited in practicality. They couldn’t be directed during flight and relied entirely on the wind. By the early 19th century, showmen paraded these balloons through towns, turning them into public spectacles that captured the attention of potential customers. As the novelty faded, showmen resorted to more daring stunts, taking horses—and even their own wives—into the sky to maintain interest.

Aiming Higher:

The Victorians were captivated by ballooning, with adventurers and scientists pushing the boundaries of how far and high they could fly. Charles Green stood out as the most famous Victorian aeronaut among these pioneers. He funded his passion for ballooning through public demonstrations and offering passenger flights from London’s fashionable gardens. In 1836, he achieved a historic milestone by launching from Vauxhall Gardens and flying all the way to Nassau, Germany.

For scientists, balloons were invaluable, providing the only way to conduct experiments at high altitudes. As they explored the upper atmosphere, they pushed their balloons to ever greater heights. Henry Coxwell and James Glaisher once ascended to nearly 30,000 feet, where they both suffered from hypoxia—oxygen deprivation. Glaisher lost consciousness, leaving Coxwell to battle fading senses and numb limbs. In a desperate move, Coxwell used his teeth to pull the gas valve line, releasing enough gas to bring them safely back to earth. Not all balloonists, however, were as fortunate.

Military Use:

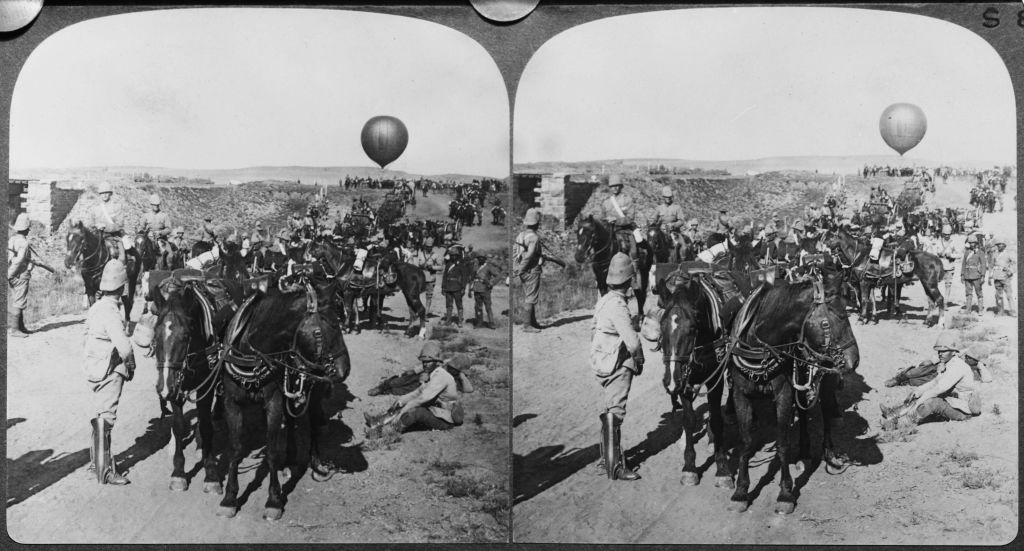

Balloons have seen various uses over time. Most notably, the military employed them as observation platforms, starting with Napoleon in 1794 and later during the American Civil War and the Boer War in South Africa.

Parisians also used balloons to escape the Prussian siege in 1870, carrying mail and even using carrier pigeons to send messages back to the city. Balloon designs continued to improve, with larger models built to entertain and transport the public at significant expositions that thrived in Europe during the late 18th century.

The emerging science of photography also took to the skies, giving birth to aerial photography. Yet, despite these advancements, no one had yet devised a way to propel and steer balloons effectively.

The Zepplin Airship:

The challenge of creating a steerable, or “dirigible,” balloon lay in developing a propulsion system that was both powerful and light enough for sustained flight. Henri Giffard flew a small steam-powered airship as early as 1852, but lacked sufficient power. Additionally, the idea of a steam engine operating beneath a hydrogen-filled balloon was far from ideal. Other inventors tried electric motors, but the power-to-weight ratio remained inadequate.

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, a retired Prussian cavalry officer, ultimately found the solution. Fascinated by balloons since encountering them during his service in the American Civil War, Zeppelin imagined linking several balloons together in a streamlined, steerable “sausage” shape. The Zeppelin airship was born by combining this design with newly developed internal combustion engines.

The first of his airships, 420 feet long and made up of multiple gas cells enclosed in a lightweight aluminum framework covered with canvas, took flight from Lake Constance in July 1900. Though early models were prone to accidents, the Zeppelin steadily improved. It became the first to offer regular passenger air service, served as a military “terror” weapon in World War I, and eventually evolved into the sleek transatlantic airships of the 1920s and early 1930s.

Let The Race Begin:

During that time, ballooning was taken in by the new playboys in the Edwardian era—balloon meetings and races were the rage among the young, rich men of that era. The most notable of these races was the annual long-distance race orchestrated by the American publishing tycoon Gordon Bennett. Having started in 1906, it continued with success until WWII came.

By 1971, the balloons had revived, yet its old rival knocked the gas balloon off, and the hot air balloon had returned!

The Surge Came Back:

The first modern hot-air balloon took flight in 1953, signaling the start of a remarkable resurgence in ballooning. This revival was primarily driven by combining two key technologies: lightweight, airtight nylon fabrics and powerful propane burners that efficiently heated the balloons.

Globally, these vibrant balloons have transformed into colorful dots in the sky, featuring imaginative designs that range from beer bottles to flying cows. The possibilities are endless, and thousands of people worldwide continue to enjoy the sights and excitement of ballooning.

If you’ve never been before, consider adding the Plano Balloon Festival to your bucket list. It’s a spectacular event each year that the whole family and friends can enjoy! They even offer tethered rides—a hot-air balloon anchored by a rope—so if you’re not quite ready to soar high into the sky, you can still experience what it’s like to be in a hot-air balloon.

Sources:

History of Ballooning: https://www.planoballoonfest.org/p/about/history

Festival Facts: https://www.planoballoonfest.org/Facts