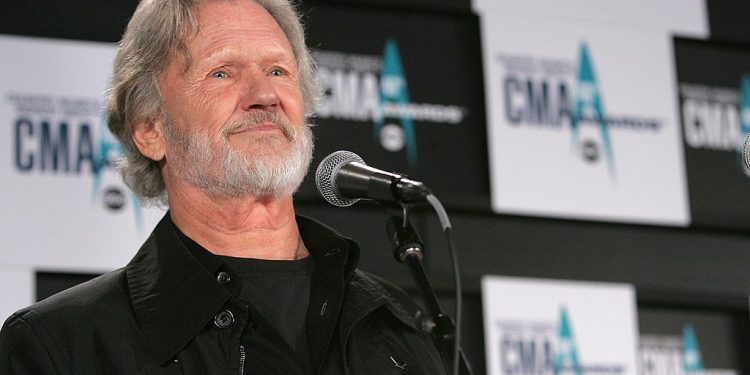

By ANDREW DALTON AP Entertainment Writer

LOS ANGELES (AP) — If Kris Kristofferson’s life were fiction, it would feel a little implausible. He was a Texas-born Golden Gloves boxer and star football player, a Rhodes Scholar and a helicopter-flying U.S. Army captain who walked away from a West Point faculty gig to briefly become a janitor on his way to becoming one of the greatest American singer-songwriters of the 20th century.

And, as if just for kicks along the way, he became a devilishly handsome major movie star who could play either a rugged outlaw or a romantic leading man.

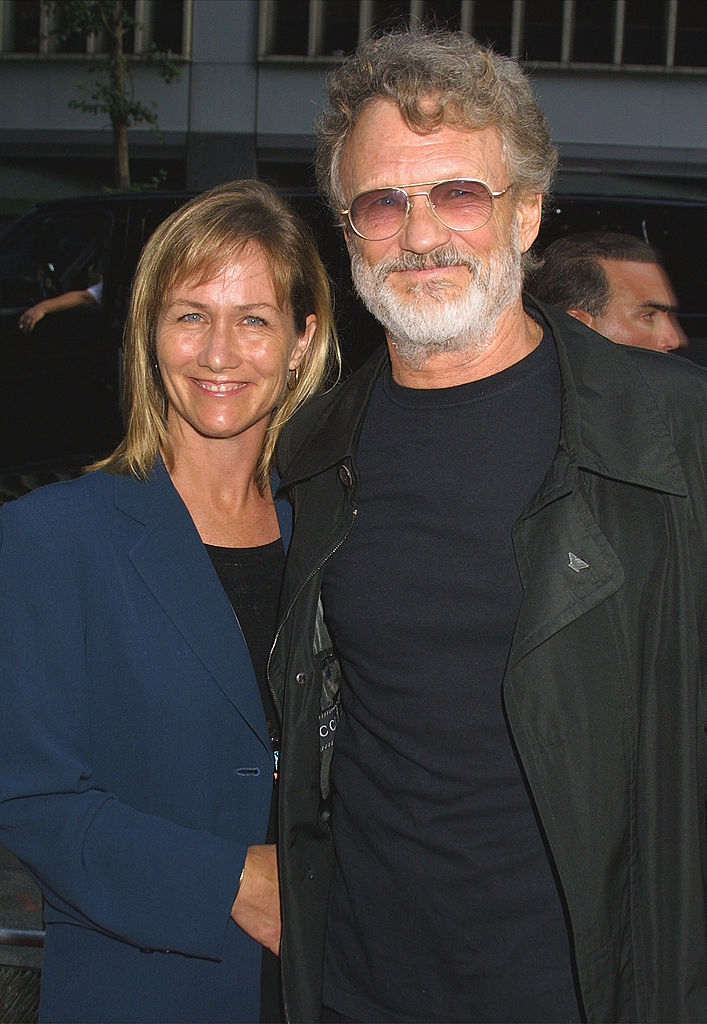

Kristofferson, a father of eight children who was married to third wife Lisa Meyers for the last four decades of his life, died at his home on Maui, Hawaii, on Saturday at age 88, surrounded by family.

He had a master’s degree in English from Oxford and could quote the poetry of William Blake from memory. One of his best songs, “The Pilgrim,” probably played on “The Pilgrim’s Progress” from a even older English writer, John Bunyan. Kristofferson’s title character could be a description of himself:

“He’s a walking contradiction partly truth and partly fiction, Taking every wrong direction on his lonely way back home.”

Though the “lonely” part certainly didn’t apply. Kristofferson never lacked for friends, including heroes who became mentors and close companions, like Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson.

While walking away from the Army, he swept floors and emptied ashtrays at Columbia Records in Nashville to get access to stars, including Cash.

He told the Associated Press in 2006 that he likely would not have had a career without the Man in Black, who would record the best-known version of Kristofferson’s “Sunday Morning Coming Down.”

“He kind of took me under his wing before he cut any of my songs,” Kristofferson said. “He cut my first record that was record of the year. He put me on stage the first time.”

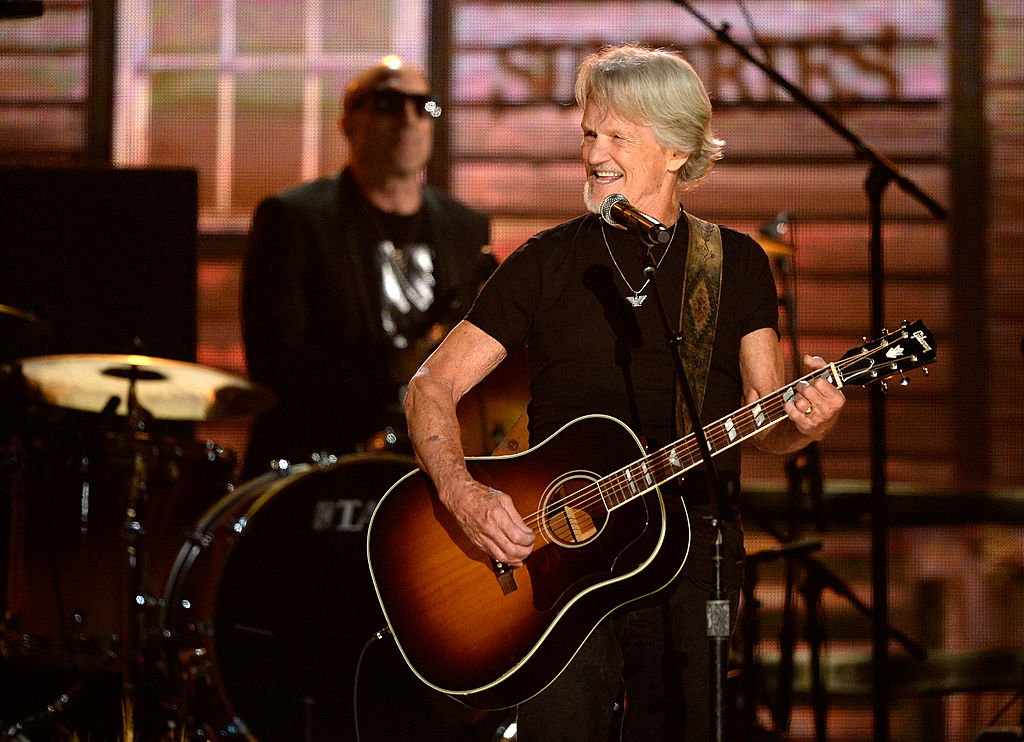

Kristofferson was a major performer and hitmaker in his own right, but never had the golden voice that some of his friends did.

Nelson used an entire album of Kristofferson songs to show his vocal mastery, and a few — including “Loving Her Was Easier (Than Anything I’ll Ever Do Again)” — became lifelong live staples.

“There’s no better songwriter alive than Kris Kristofferson,” Nelson said in a 2009 awards show tribute. “Everything he writes is a standard.”

Kristofferson, more comfortably than anyone, straddled the worlds of classic country music and Baby Boomer hippie culture. Janis Joplin was another close friend, and her howling rendition of Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee” would become a hit soon after her death in 1970. It was probably the best known version of any Kristofferson song, and he would use her arrangement of it when he played the song live.

Kristofferson also embraced kindred spirits of younger generations, like Sinead O’Connor.

A critic of the Roman Catholic Church well before allegations of sexual abuse were widely reported, O’Connor was loudly booed at a Madison Square Garden tribute to Bob Dylan in 1992, two weeks after ripping up a picture of Pope John Paul II while appearing on “Saturday Night Live.”

Kristofferson would come out and walk her off stage in solidarity and solace. Years later, he recorded “Sister Sinead,” in which he wrote, “And maybe she’s crazy and maybe she ain’t, But so was Picasso and so were the saints.”

His leftist politics may have been the greatest of his “contradictions,” coming from a country-singing Army veteran from Brownsville, Texas. He was a staunch supporter of Palestinians and made heated denunciations of many military actions in Central America and the Middle East from the stage, sometimes to the chagrin of audiences. He clashed at times with more hawkish stars like Toby Keith, though he counted many conservative country stars as friends and supporters.

Kristofferson said during a 1995 interview with the AP he remembered a woman complaining about one of his songs that talked about killing babies in the name of freedom.

“I said, ’Well, what made you mad — the fact that I was saying it or the fact that we’re doing it?'” Kristofferson said. “To me, they were getting mad at me ’cause I was telling them what was going on.”

To him, there was no contradiction, his political thinking was a reckoning for his military past.

“When you come to question some of the things being done in your name,” he told the AP in 2006, “it was particularly painful.”

No one was upset by the man’s blue-eyed gaze on screen, however. Legendary Western director Sam Peckinpah saw him as a perfect young outlaw to put alongside James Coburn in 1973’s “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.”

But he would be best known for playing the handsome love interest in films that centered on strong women: Ellen Burstyn in 1974’s “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,” directed by Martin Scorsese, and Barbra Streisand in the 1976 version of “A Star Is Born,” a role echoed by Bradley Cooper in the 2018 remake.

Streisand said on Instagram that she was developing “A Star is Born” when she saw Kristofferson on stage at the Troubadour in Los Angeles.

“I knew he was something special,” she wrote.

Scorsese said Monday that Kristofferson was “a damn good actor, a remarkable screen presence. Spending time with Kris when we made ‘Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore’ was one of the highlights of my life.”

The director said in a statement that he was listening to “Me and Bobby McGee,” “Just like half of the world.”

Kristofferson became a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2004, but he had already been canonized beyond his own satisfaction when he became a member of the supergroup the Highwaymen in the mid-1980s, alongside Cash, Waylon Jennings, and Nelson, the only member now alive. To Kristofferson, it meant the men he had admired most regarded him as an equal.

“To be not only recorded by them but to be friends with them and to work side by side was just a little unreal,” Kristofferson told the AP in 2005. “It was like seeing your face on Mount Rushmore.”

Nelson and Cash’s daughter Rosanne were among the many artists who took part in a 2016 tribute concert to Kristofferson, joining him on stage for a group rendition of his song “Why Me.”

Kristofferson long thought about he would like to be remembered.

Another friend, Leonard Cohen, wrote in liner notes to his greatest hits collection that Kristofferson once told him he wanted the opening lines of Cohen’s “Bird on a Wire” on his tombstone: “Like a bird on a wire, Like a drunk in a midnight choir, I have tried, in my way, to be free.”

It’s apt enough, but another Kristofferson line from the “The Pilgrim” might serve just as well:

“The goin’ up was worth the comin’ down.”