Cowboy culture runs deep and is iconic to America—especially Texas. However, not many people know how cowboys got their start or how the occupation evolved into a vital part of American history and identity.

We often see the All-American cowboy saving the day in Hollywood movies, but the film industry tends to omit the significant role of the Vaqueros, who laid the foundation for many traditions still in use today.

Meet the Vaqueros

Who were the Vaqueros? The term “Vaquero” is Spanish for “cowboy,” with vaca meaning “cow” and -ero denoting “worker.” The Vaqueros predate 1836, the year Texas declared its independence. Like much of modern American history, their story intertwines with the arrival of European colonizers, which fundamentally altered the relationship between the people and the land.

To fully appreciate the Vaqueros’ contribution, we must also consider the role of horses. While it’s commonly believed that there were no horses in the Americas before European contact, some experts suggest otherwise, proposing that horses once roamed the continent but became extinct before the arrival of Europeans.

The story of the horse’s return begins with Christopher Columbus, who brought horses to the Americas in 1492. By 1519, the indigenous populations in what is now Mexico encountered horses brought by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. These Spanish horses, known for their resilience and agility, would later become the mustangs that roamed the open grasslands.

The Reason the Spanish Wanted Horses in Mexico

In 1521, Gregorio de Villalobos, a Spanish viceroy, brought cattle to New Spain (modern-day Mexico) as a source of food. The descendants of these cattle eventually became the Texas Longhorns we recognize today.

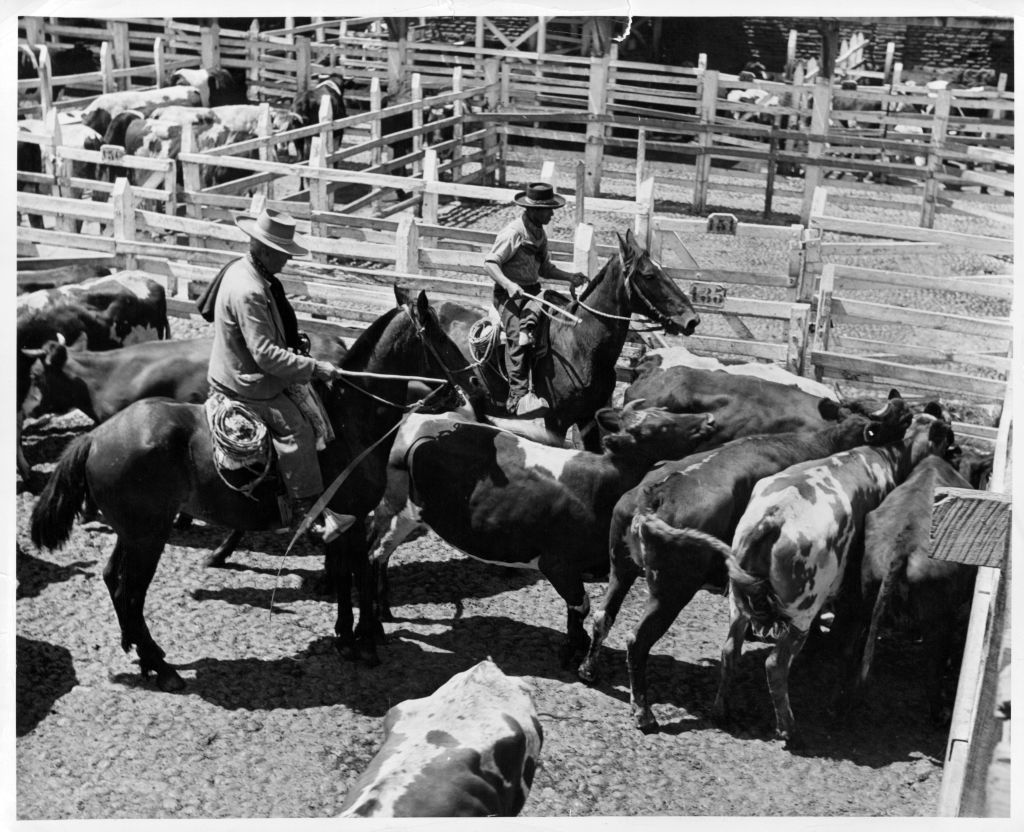

Both cattle and horses thrived in the region, which created a demand for more workers to manage the growing populations. Cattle often escaped their enclosures, making it necessary to round them up. To combat this, the Spanish looked to the indigenous Mexican population, who became a crucial part of this ranching culture, a tradition that later became deeply ingrained in Texas heritage.

By the 16th century, the vaqueros became farmers and ranch laborers having mastered cattle management. Although they initially lacked European-style saddles, they quickly adapted, blending their skills with techniques like buffalo hunting to create a unique and enduring tradition.

The Value of Vaqueros in Texas History

Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, and Texas (then called Tejas) became a Mexican province. The Mexican government encouraged immigration from the United States, inadvertently fostering a desire for Texan autonomy.

In 1836, Texas declared independence. Within ten years, the state was annexed by the United States, which brought an influx of settlers and led to the displacement of many Mexicans, with land being taken. This annexation also precipitated the two-year Mexican-American War, a conflict that served as a backdrop for the expansion of ranching culture in Texas.

From the 1850s through the 1860s, during the American Civil War, two entrepreneurs—Richard King and Mifflin Kenedy—saw an opportunity in South Texas. They partnered to buy vast tracts of land with the goal of establishing ranches. However, neither had experience with livestock, so they turned to the Mexican vaqueros for help. As families moved to farms, the vaqueros passed down their knowledge to the emerging generation of American cowboys, which was initially imparted by the Spanish. Thanks to the groundwork laid by the Vaqueros, King, and Kenedy were able to establish the U.S. ranching industry, ultimately paving the way for the iconic Texas cattle drives of the 1860s through the 1890s.

Two Iconic Trails For Cattle Drives back then:

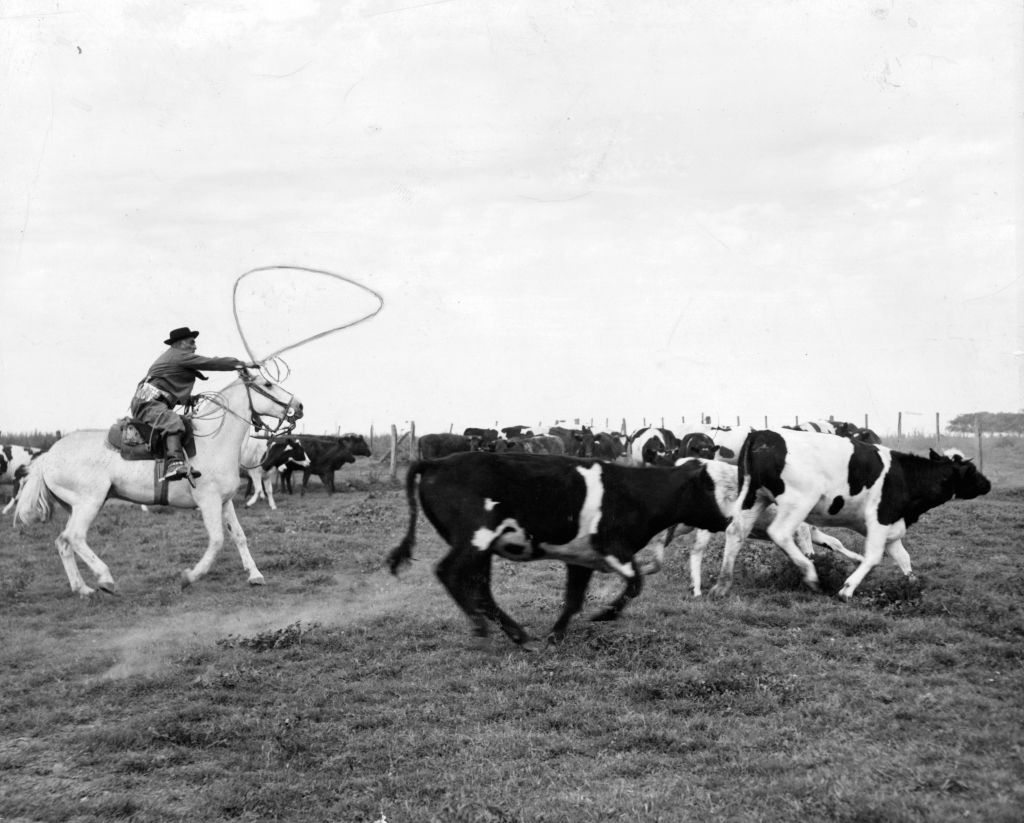

In the 1860s, America’s growing appetite for beef made the Texas Longhorn a cornerstone of the beef industry. Texas, with its abundance of cattle, became the starting point for massive cattle drives. Vaqueros and cowboys herded an estimated 5 million cattle northward, cementing these drives as a defining feature of Texas culture.

To transport cattle safely and efficiently, well-established trails were essential. While various routes were used, two trails became particularly iconic: the Chisholm Trail and the Goodnight-Loving Trail.

The Chisholm Trail

The Chisholm Trail was founded by Jesse Chisholm in 1865. Cowboys and vaqueros first used it to drive cattle north in 1866. Initially, the trail began near San Antonio, but by the mid-1870s, it extended from the Rio Grande near Brownsville, Texas, to Abilene, Kansas.

The trail’s endpoint in Abilene was strategic due to the presence of railroads, which facilitated the transport of cattle to other parts of the United States and provided access to buyers. The Chisholm Trail was most popular in 1871 but saw a decline in use by the mid-1880s as railroads expanded into Texas. With rail transport available locally, vaqueros and cowboys no longer needed to drive cattle long distances to northern railheads.

The Goodnight-Loving Trail

The Goodnight-Loving Trail, with its evocative name, was named after Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving. The trail gained popularity among cowboys and vaqueros as a reliable route to transport cattle to New Mexico and Colorado, effectively opening the way to the western markets.

Goodnight and Loving initially planned to drive their cattle from North Texas to Denver. However, the route posed significant challenges, as the areas between Denver and North Texas were fraught with dangers from hostile Native American tribes. To address this, the two men devised a safer, though longer, path.

On June 6, 1866, Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving set off on their first journey to Denver with 2,000 head of cattle. They followed an old Butterfield Stagecoach route southwest, traveled along the Pecos River, and then headed north into Colorado.

Their efforts paid off, as they successfully avoided conflicts and arrived in Denver with their cattle intact. The Goodnight-Loving Trail quickly gained recognition as a safe and effective route for transporting cattle westward, securing its place in history alongside the Chisholm Trail.

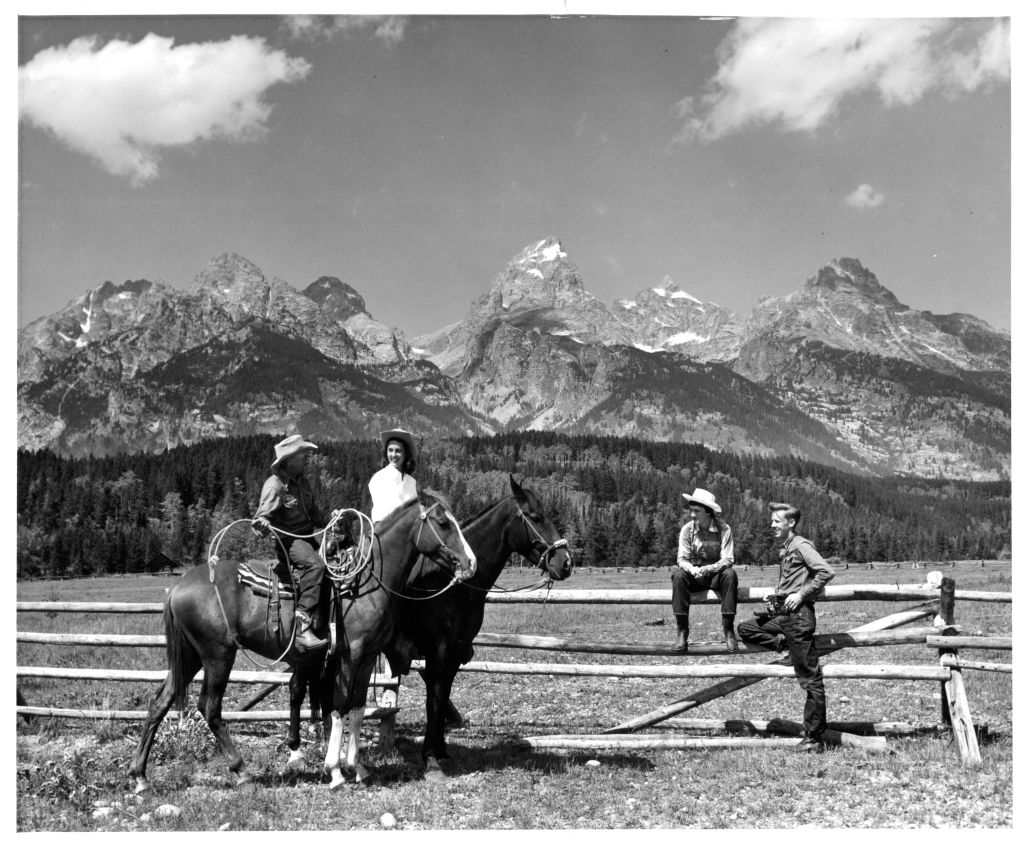

Cowboys & Vaqueros

Cowboys and Vaqueros are both celebrated as expert horsemen skilled in managing cattle from horseback. They shared similar responsibilities, such as maintaining ranches, repairing corrals, and tending to livestock. Both required proficiency in roping runaway calves or horses and herding cattle. Their lives are often romanticized as days spent traveling trails, nights under starry skies by a campfire, and constant care for animals.

What sets them apart is the Vaqueros’ longer history, rooted in Spanish influence. One notable difference is their attire: Vaqueros traditionally wore large sombreros instead of the now-iconic cowboy hats. The sombrero provided essential shade from the intense sun of Mexico and Texas. Vaqueros also carried serapes, versatile tools used to direct wandering cattle and as blankets during cold nights.

Vaqueros favored boots with heels, which differed from the flat, square-toed boots often worn by drovers. They also commonly wore pocketless vests. Another hallmark of the Vaquero tradition was their skill in riding without saddles, using braided rope made from horsehair and leather hides to fashion their own. This technique called lazo in Spanish, evolved into what is now known as the lasso—a tool integral to catching wild horses.

Vaqueros frequently showcased their lassoing expertise in competitions, a precursor to one of Texas’s most iconic traditions: the rodeo.

Cowboys, while distinct in style and culture, inherited many skills and traditions from the Mexican Vaqueros. Generations of knowledge passed down preserved these practices, blending them into what became a uniquely Texan way of life. Over time, cowboy culture developed its own hallmarks, including smaller cowboy hats, riding bucking broncos and bulls, and a love for storytelling around the campfire.

Interestingly, even the term “buckaroo” originates from the Vaquero legacy. Non-Spanish speakers often struggled with the pronunciation of vaquero (ba-care-oh), leading to the simplified and enduring nickname “buckaroo.”

Notable Cowboys

In addition to Oliver Loving and Charles Goodnight, several other notable cowboys have left their mark on history.

As previously mentioned, the Spanish-Mexican Vaqueros were the first cowboys in Texas. They pioneered the equipment and techniques that would later become integral to Texas culture and ranching traditions.

Francisco García

Francisco García played a pivotal role in Texas cowboy history by organizing the first recorded cattle drive in the region. This event was tied to the American Revolution, as General Bernardo de Gálvez, fighting the British along the Texas coast, needed supplies to feed his troops.

In 1779, García was tasked with organizing a cattle roundup and subsequently led a drive of 2,000 cattle from San Antonio along the Old Spanish Trail to New Orleans. This effort not only provided crucial supplies to the Spanish army but also established a trade route between Louisiana and Texas. The Spanish ultimately defeated the British along the Gulf Coast, solidifying García’s contribution to history.

Bose Ikard

The long history of cowboys also includes African American cowboys, many of whom were formerly enslaved individuals. One prominent figure is Bose Ikard, who was born in Mississippi and moved to Texas in 1852.

After the Civil War, Ikard worked for Oliver Loving and Charles Goodnight, becoming a trusted and indispensable member of their operations. His reliability was so renowned that he was often entrusted with transporting large sums of money.

Charles Goodnight held Ikard in the highest regard, once stating that he trusted him more than any living man. When Ikard passed away, Goodnight personally commissioned his headstone with the following inscription:

“Served with me four years on Goodnight-Loving Trail. Never shirked a duty or disobeyed an order. Rode with me in many stampedes. Participated in three engagements with Comanches.

Splendid behavior.

Goodnight”

Ikard was laid to rest in Weatherford, Texas, in the same cemetery as Goodnight. He was later inducted into the Texas Trail of Fame, and a statue honoring him now stands in the Fort Worth Stockyards.

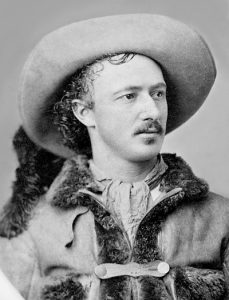

John Baker “Texas Jack”

John Baker, better known as Texas Jack, was a man of many talents and roles. He served as a scout during the Civil War, a cowboy, a trail guide for the U.S. Cavalry, a hunting guide for royalty, a frontier reporter, and more. His cowboy career began as a trail driver after the Civil War.

With such an eclectic background, Texas Jack wrote vividly about his life as a cowboy and his adventures in letters to the New York Herald. His stories captivated the public and earned widespread admiration. Due to the popularity of his tales, Texas Jack became the subject of numerous short novels. Although his life was tragically cut short, his legacy endures, and he remains a notable figure in cowboy history.

Honoring the Legacy

The legacy of cowboys and Vaqueros continues to shape the cultural identity of Texas and the broader American West. Their resilience, ingenuity, and sense of adventure created a way of life that still resonates today. Their contributions remain timeless from the practical skills of herding cattle and riding trails to the romanticized stories of their lives under open skies. Whether through rodeos, historical reenactments, or monuments honoring figures like Bose Ikard and Texas Jack, their spirit lives on as a testament to a rich and enduring tradition.

Sources:

Texas Cattle Drives

https://tpwd.texas.gov/education/resources/keep-texas-wild/vaqueros-and-cowboys/texas-cattle-drives

Mexico’s Original Cowboys

https://amigoenergy.com/blog/mexicos-original-cowboys-history-of-the-vaqueros-of-texas/

Famous Cowboys

https://texasproud.com/famous-texas-cowboys/